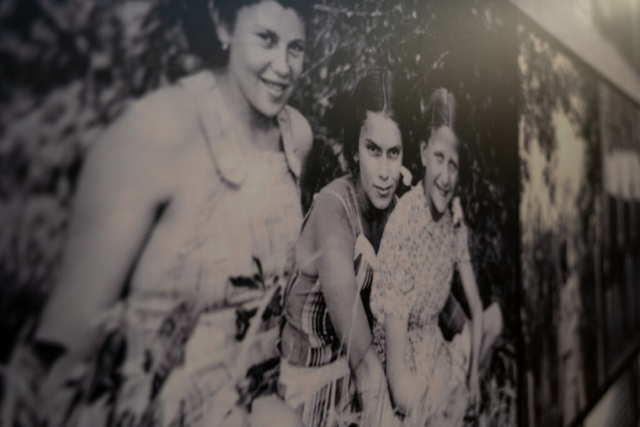

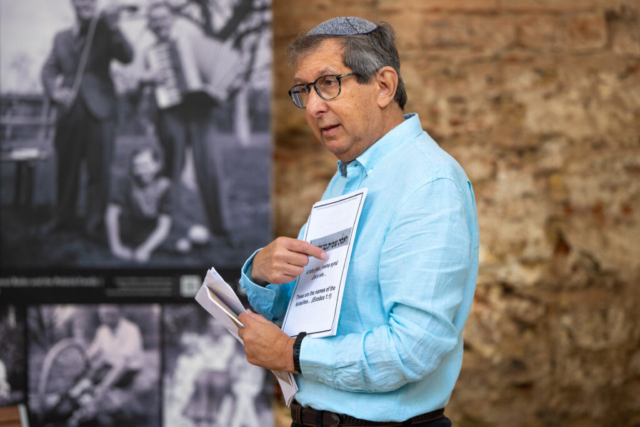

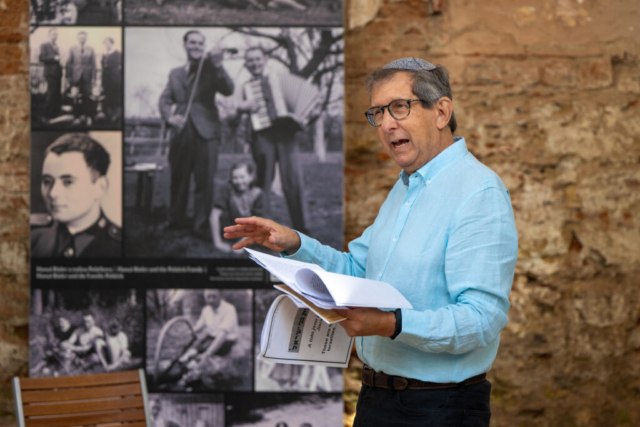

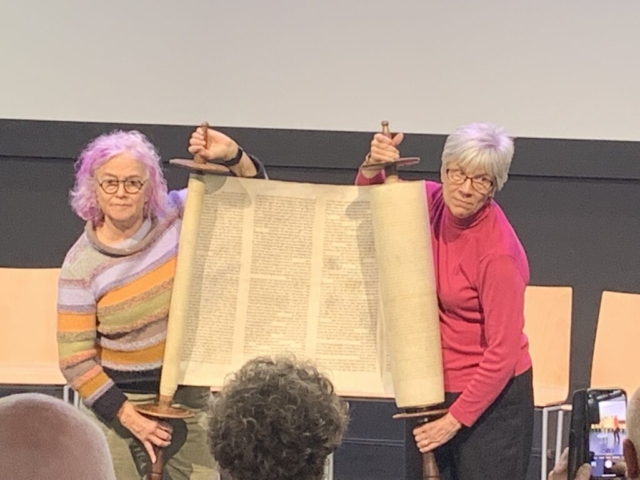

Nelly Gutmann – the 98-year-old daughter of the last rabbi of Pacov – and her family now live in Kibbutz Dorot, just 15 km from southern Gaza. The terrible Hamas attack on October 7, 2023 have affected her too and changed her life, her feelings and her thoughts from one day to the next and forever. You can listen to what Nelly herself and her family members of different generations think about their present and future and how they assess the chances of living together with their Palestinian neighbors after October 7th in this moving ARTE video:

https://www.arte.tv/en/videos/118276-000-A/israel-from-the-holocaust-to-gaza/