the life story of Hanuš Bader

Hanuš Bader in Sweden

Hanuš Bader was one of the few Holocaust survivors from Pacov who had been sent to Terezín in November 1942. He survived the concentration camp in Auschwitz and Schwarzheide Labor Camp to be deported to the Bergen-Belsen death camp towards the end of World War II where, on the brink of death, he was liberated by British troops.

Hanuš Bader was born on July 2, 1914 in Brno, Moravia. He spent his youth in the small town of Miroslav, approximately 28 miles (45 kilometers) southwest of Brno, where his father Max Bader ran a café. His mother, Emilie Baderová, née Poláčková, was born in Pacov. Emilie’s sister Berta was married to Emil Lederer, and her brother, Ludvík Poláček, owned a general store in Pacov. When Hanuš was 15, his father died.

Having completed his primary education in Miroslav, Hanuš spent four years with his relatives in Pacov where he attended lower secondary school. He then returned to Miroslav to work as a clerk in a liquor company. From 1936 to 1938 he served in the 24th infantry regiment in Znojmo, in Southern Moravia, where he attended military academy and was upgraded to the rank of corporal. Several photographs dating from the time when he served in the Czechoslovak Army show a handsome young man. According to the testimony of his son, many local girls kept copies of his photo.

Ludvík Poláček’s store in Myslíkova street No 48, August 1927

In September 1938, because of the continued Nazi threat, Hanuš was not demobilized and remained in the service of the army. He was then transferred to a mobilization office in Jihlava. After the Munich Treaty the town of Miroslav ended up in an occupation zone and Hanuš and his mother moved to Pacov where they rented a small flat. Hanuš started working in his uncle’s general store.

We were forced to stand facing the wall all the day long

In March 1939, Hanuš’s life was affected by the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia, as were the lives of other Czechoslovak Jews. In September 1940, he and his uncle, Ludvík Poláček, were arrested by the Gestapo. According to his memoires: “One day, three Gestapo men came to Uncle Poláček’s house. They shut the door and told us, including my visiting mother, to line up in the kitchen. They then ordered us all to present ourselves at a Gestapo office in three days at Německý (German) Brod, today’s Havlíčkův. We went there by train and after reporting they ordered us to line up facing the wall the entire day until the evening. Every two hours the guards took turns marching behind our backs with a whip in hand. If anyone moved a bit they whipped our backs and our heads. My mother became very tired and I insisted that she hold on, as I did not know what might otherwise happen.

Later in the evening they took us to jail, separating men and women. There were fourteen people in our room. In the morning and evening they let us walk in the backyard for 20 minutes. For breakfast we had a piece of hard bread and some black water they called coffee. For lunch we were served a cup of soup. The entire day we were ordered to continually march around the room. Uncle Poláček and I were the only Jews there, as the other prisoners were Czechs, including a university professor who advised us not to talk as one of the prisoners was allegedly an informer. Every afternoon the alleged informer washed dishes in the office and reported what was going on in our jail cell. We were very cautious.

Hanuš Bader prior to the war

The worst thing was that we did not know what happened to my mother and Uncle Poláček’s wife. One morning the door opened and a member of the Gestapo asked Uncle Poláček and I to come along with him. We were frightened as we did not know what this meant. It happened quite often that a prisoner would be called out and would not be seen again. We would then hear a gunshot as they were executed in the backyard. Fortunately, this time it was different. They took us to the garage where they had us wash and polish their cars. Our guard even gave us some cigarettes and then left us alone. They knew very well we would not escape as we could not get very far. We cleaned the cars very carefully and spent several days doing this. In the evenings we always brought some cigarettes to our comrades.

One day the guard pointed to me: ‘Only you!’ He took me to the office and there I was told I could return to Pacov. I was very upset and asked when Mr Poláček would come home. Until today I do not know how I could have even dared to ask such a question. Within several days they gave me my belongings, including a railway pass, and I left for Pacov. My mother and Aunt Marta cordially greeted me and were especially pleased to hear that my Uncle Poláček would return home in a couple of days. The next day I started to work in my uncle’s shop again.

However, my uncle did not show up. After several weeks we received a postcard from Pankrác jail in Prague that said, ‘I am now in Prague. I am ok and you are allowed to visit me once every month.’ In about three weeks my Aunt Marta and I went to Pankrác to visit my uncle and received a brief reply when we asked to visit him: ‘There is no Poláček here and we cannot provide any other information.’ Although the Jewish Community Office was often informed directly by the Gestapo, they couldn’t tell us where my uncle had been relocated to. In a couple of days an Obersturmführer, member of the Gestapo, from Tábor came to tell Aunt Marta that her husband had died in Dachau of pneumonia, and that we could get his ashes if we would pay twenty-five German marks. My aunt collapsed with grief. We sent the money to a bank account in Prague and several weeks later we received a clay urn with ashes, which we buried in the Jewish Cemetery in Pacov. Who knows whose ashes they were…”

Miraculous escape from Auschwitz

Nelly Guttmann, the daughter of Pacov’s Rabbi Natan Guttmann, was fourteen at the time of Ludvík Poláček’s arrest and could not understand how it was possible that an entirely healthy man could die in just several weeks. Ludvík Poláček’s death illustrates an atmosphere, full of uncertainty and fear, in which the Jews of Pacov were living at that time. Emil Lederer, another of Bader’s uncles, had been previously arrested in 1940. Lederer died two years later in the “euthanasia center” in Bernberg, where he was sent from the concentration camp of Buchenwald. He was transported to Bernberg, ill from exhaustion, only to be killed in the gas chamber. His family members were also “allowed” to buy an urn with his ashes, which they burried in the Pacov cemetery. Věra Ledererová, the only one of the entire family who survived the Holocaust, arranged for a tombstone for Emil Lederer and Ludvík Poláček, as well as for her husband Egon Kaufmann’s family.

Discrimination and oppression of Jewish communities in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia continued with “Arisierung” (expropriation), targeting German Jews and their property, which included Ludvík Poláček’s store, now managed by his nephew Hanuš Bader. A local Czech Nazi collaborator tried to take over the business, but Hanuš Bader succeeded in getting permission from the Protectorate authorities to wind up the business. Thus, Bader managed to save the house and many of the goods from his store including meat tins, coffee, sugar and rice, which he traded for fresh food with local farmers. This enabled the family to survive the period in which there was a lack of food. The rations for Jews were greatly reduced in comparison to other Protectorate citizens.

The period of uncertainty and fear culminated on November 16, 1942. On that day, all Jews living in the Tábor region were transported to Terezín (Theresienstadt) in Central Bohemia. The Jews from Pacov were first sent to a school building in Tábor where they spent the entire night standing. The next day they continued to Terezín by train.

In Terezín, Hanuš Bader met his future wife, twenty year old Inge Markusová from Brno. In December 1943 he, together with his wife and his mother-in-law, were sent to the so-called ”Family Camp” of Czechoslovak Jews in Auschwitz-Birkenau. After their arrival they were kept in a quarantine camp before their release into the family camp. Although families were separated into different barracks, they were allowed to meet with each other in the evening. Hanuš Bader’s mother, who had been sent to Auschwitz several months earlier was so skinny that her own son did not recognize her. Old and ill prisoners were regularly selected and killed in the gas chambers. Both Hanuš’s mother and his mother-in-law shared the same fate of dying in the gas chambers.

Hanuš Bader’s health condition deteriorated rapidly. On two separate occasions he fell ill with penumonia which left him skinny and weak. However, in July 1944, he was chosen as one of the “lucky ones” to work in the Schwarzheide Labour Camp in Germany, near the secret plant BRABAG (Braunkohl-Benzin-Aktion-Gesellschaft), where petrol was produced from brown coal. The plant had been bombed and severely damaged by the Allies and the prisoners were forced to rebuild it.. However, they suffered from the lack of food, clothing, and shoes. Hanuš Bader hurt his leg and was suffering from blood poisoning. He was nursed to health by another Jewish prisoner, a medical doctor, who courageously refused to amputate his leg. In February 1945, all prisoners were deported to the Bergen-Belsen camp in the north of Germany. The camp was overcrowded and there was no food, medications, or medical care. Hanuš Bader became infected with typhus and had water in his lungs, but survived to see the camp be liberated by British troops on April 15, 1945. He was the only survivor out of three-hundred prisoners deported from Schwarzheide.

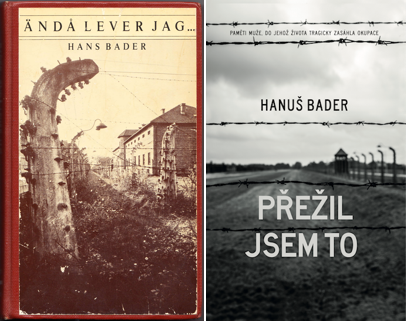

Swedish and Czech editions of Hanuš Bader’s memoires

On June 28, 1945, Hanuš was taken to Malmö in Sweden by the Swedish Red Cross along with other Czechoslovak citizens imprisoned in concentration camps. His wife Inge survived as well, and came to meet him in Sweden, but she soon died of tuberculosis on September 21, 1945. She is burried in the local Jewish cemetery in Malmö.

Hanuš (Hans) Bader was married twice in Sweden, first to Sonja Dorisk Majken Thörn and later to Margit Wedin. In 1949 his son Stefan was born in Malmö, where he currently resides. In 1977 his father’s memories “Ändå lever jag” (And Yet I Live) was published in Swedish and in September 2018, a Czech translation was published in Prague. Hanuš Bader died on October 16, 2002.

✡