Nelly Prezma née Guttmannová talks about her childhood in Pacov in the interwar Czechoslovakia

Nelly Prezma née Guttmannová (90) recalls her childhood in Pacov before World War II, the transportation of the local Jewish residents to concentration camps, and her return to Czechoslovakia after the war. The interview was conducted by Eva Sobotka in Israel where Ms Prezmah lives since 1948.

Nelly Prezma née Guttmannová (90) recalls her childhood in Pacov before World War II, the transportation of the local Jewish residents to concentration camps, and her return to Czechoslovakia after the war. The interview was conducted by Eva Sobotka in Israel where Ms Prezmah lives since 1948.

Also published by the Z mého kraje monthly in May 2017, and in an abridged form by the Pelhřimovský deník daily on January 27, 2017 (both Czech only).

You grew up in Pacov, Czechoslovakia, during the interwar period. How do you remember those times? Can you tell us more about your family background?

I wasn’t actually born in Pacov but moved there when I was 2½ years old. I went to nursery then elementary school in Pacov until 1939 when the Germans came and I was expelled. I was 13 at the time.

I lived with my sister Růža, my mother Žofie, and my father Nathan who was the local rabbi and religious teacher. He was highly respected not just by the Jews but by all the inhabitants of Pacov because he often helped them. Pacov was a small town, almost entirely inhabited by farmers and potato growers who had no idea or understanding of bureaucratic procedures, so my father helped them out. We were all like one big family, really. I had Gentile friends and went to a Czech school. My mother was a qualified nurse but she didn’t have a job. She was a housewife.

We lived in 315 Malovcova Street. We weren’t Orthodox; my father was a Reform Jew. We also went to school during Jewish holidays and the Sabbath. We celebrated the Sabbath during school holidays only. We participated in all school activities and skipped school only during the main holidays: Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Passover. The teachers understood we wouldn’t go to school during those. We got on very well with everyone there.

Do you recall some of the Jewish families you were best acquainted with?

There were about thirty Jewish families in Pacov. They were all quite well off, affluent. There were merchants and farmers too.

I remember the Schecks, the synagogue warden’s family. The Glasers had a big farmstead and I think they had three children but the only one I remember is their little girl, who was very pretty. Then there were the Wieners, shopkeepers, who had a son called Jindra. Mr Wertheimer the lawyer had a son called Milan. The Lederers had two daughters, Zdeňka and Věra. The Jokls had a son called Vláďa and ran a haberdashery. The Syneks also had a son but I don’t recall his name. The Gross family lived in the main square, owned a hardware store and had one or two sons but I forget their names. And then there were the Pachners.

One of my father’s best friends was a Roman Catholic dean

What were the relations between the Jews and Gentiles in Pacov as you recall them?

I had a friend in Pacov. Her parents were ordinary people. Her father bred horses. Her mother worked as a cleaner before the Germans arrived. When the Germans came, my friend’s father said: “Don’t worry, we’ll protect you. We don’t care for the Jews in Tábor, though; let them go.” He didn’t know any other Jews since he had never set foot outside Pacov. One family even gave their daughter a Jewish name, just to show friendliness towards the Jews.

Nelly Guttmann (middle right) along with other children in front of the former Jewish school in Pacov (1937).

I should like to mention that one of my father’s best friends was a Roman Catholic dean. They often talked about the Bible, the dean discussing the New Testament and my father the Old Testament. We really had a very good life there. Although of course there were some anti-Semites there, too, especially before the Germans came.

I had a teacher whom I deeply respected. In those days children used to respect their teachers, unlike today when everybody is overfamiliar with everyone else and people address each other by their first names. We used do things differently. Teachers were respected by everyone. Children who failed to acknowledge their teacher in the street would be punished. During the occupation I happened to meet this teacher of mine once. I didn’t know what to do and whether to greet her or not because if someone saw me do that, she might be arrested or sent to a concentration camp. It was a great dilemma for me. But as soon as she saw me she came up to me and said hello. I found it very encouraging. I remember this teacher, Miss Urbanová, to this day.

What was the atmosphere like during the occupation?

In the late 1940 Mr Ludvík Poláček who ran a general store was arrested despite having done nothing wrong. He was taken away and transported to a concentration camp. After several weeks only his ashes arrived. They said he had died of pneumonia. I was just fourteen year old then and when I heard it, it sent me into hysterics. I burst into hysterical laughter. Then I withdrew into myself and started weeping because I just couldn’t comprehend how a healthy person could die so suddenly.

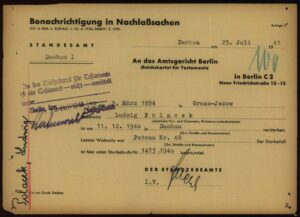

The death certificate of Mr Ludvík Poláček.

In the early day of the occupation you left for Prague and stayed there until 1941. Could you elaborate a little bit on that?

In August 1940 I went to Prague and became an apprentice milliner in Mrs Mašková’s shop in the Smíchov neigbourhood. I lived in a nearby Jewish boarding house. I had a good friend who wasn’t Jewish. We were good friends until it became compulsory to wear the Star of David. Afterwards I didn’t want to be seen with her any longer as it might put her in harm’s way. I forget her name. She lived in Prague. We used to walk to work together past the Ringer factory, where there were some Germans. Often we saw this particular German with a swastika armband who always smiled and greeted us politely. The first time he saw me with the Star of David he was quite shocked as he realized I was Jewish. (In the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia all Jews were required to wear a Star of David from September 1941 onwards – Ed.).

Nelly Guttmann, age 3, with sister Růža.

I worked in Mrs Mašková’s shop until people started threatening her because they saw me working there. She had to dismiss me. I went back to Pacov. This was in November 1941. By then my older sister Růža and her husband Arnošt Háček moved to Prague. My sister worked in a clothes shop. The Germans refused to recognize their marriage because they were married in a synagogue, not at a register office. Her husband was sent to the ghetto in Łódź and she was left in Prague on her own.

When the milliner sacked me I went back home. In those days you needed a special permission to travel, and as a Jew I had to travel in the last carriage. I decided I wouldn’t go in the last carriage and would find a seat anywhere I liked, even though I was wearing the Star of David. I found a seat in the middle carriage. The conductor saw me but he was very nice and allowed me to stay there all the way to Tábor. In Tábor I changed trains for Pacov and again sat in the middle carriage. The conductor came and told me that there were some Jews from Pacov in the last carriage. I went to take a look because I knew everyone. And who did I see? My father. He had been detained by the Gestapo in Tábor along with some other Jews. They were treated very badly, my father was thrown down the stairs, but eventually they were all released. So I said: “Come with me to the middle carriage, you don’t have to sit here, we’re human beings like everyone else and we can sit wherever we want to.” They were very scared because they’d been detained. They were older people too, so of course I joined them. We arrived in Pacov and went back home where I saw that all the windows in our flat were broken. My mother had already replaced the broken glass with cardboard. It was getting cold already. It was dreadful.

What was your life in Pacov like after that?

I stayed at home and supported my parents. My father was no longer getting his salary because he couldn’t work as a rabbi so we had no income. I went to work for another Jewish family in Pacov, the Mellers. Mrs Meller had thrombosis in her leg and couldn’t walk. She was bedridden. I cleaned their house and fed their rabbits. Then one day we were ordered to work in the Kámen village near Pacov where Jewish women and children were sent to work. We had to get up at 5am to be escorted to Kámen. We were dismantling a brickworks that used to belong to a Jew. Every morning we would get up and walk to Kámen, accompanied by soldiers with rifles. We would work until evening and then be escorted back. We had to be back home by 8pm so we wouldn’t violate the curfew.

Nelly (sitting) in front her grandfather and grandmother. On the left her father Natan Guttmann, mother Žofie Guttmannová and Nelly’s sister Růža.

However, without my father’s salary we didn’t have enough money to buy food. I had a big doll with a rococo dress, which I loved dearly. It was very special. A lady in Pacov told my mother she would give us some food in exchange for the doll. I cried and didn’t want to give it away. But after a while, when I saw we had nothing to eat, I said: “Let her have the doll so that we have something to eat.” She gave us some flour, margarine, sugar, and potatoes in exchange for the doll. During summer my mother used to go to the woods to forage for blueberries and mushrooms, which she would sell to raise money for food.

Natan Guttmann

On a Friday my mother was just cleaning the house when two Germans came. They were very polite and treated my parents very nicely. My parents spoke very good German and the Germans were surprised to hear it. My mother offered them cakes she just baked. They were very appreciative and said they would come again. They came back about a week later when we were all at home. They told me and my mother to leave the room so they could talk to my father in private. They said: “We will allow you to go out after 8pm, we’ll let you go to the cinema and theatre but only if you and your family let us know when you see other Jews outside.” My father told them we would do no such thing. They left but then they ordered him to clean the pavement and my father had to pick up dog faeces with his bare hands.

Next time they came and ordered my father to pull a cart with the Jewish manufacturer Weiner, who owned a leather goods factory in Pacov. They made Mr Weiner wear ears and a tail, put him in a cart, and forced him to beat a drum while my father dragged the cart around the main square several times. When the locals saw it, they pulled their blinds down, went back to their homes, and refused to watch.

All that evil made some people inhuman

What happened to you and your family after you were deported to Theresienstadt?

In November 1942 all the Pacov Jews were told to report for a transport. We were taken by truck to the nearby town called Tábor and from there by train to Bohušovice. From Bohušovice we walked to Theresienstadt. Later on, a railway station was built directly in Theresienstadt.

The Jewish residents of Pacov being transported from Pacov to Theresienstadt, November 1942.

In Theresienstadt I was billeted together with my mother. My father stayed somewhere else. My mother worked as a nurse but she couldn’t do much as there were almost no medications in Theresienstadt. But still, she could be of some help to the sick, who were mostly elderly. I worked in a nursery school under a Mrs Cvikrová until I was transferred to a girls’ home. We did our best to make these children’s lives a little easier. We played with them, taught them, sang songs to them and took them for walks. I remember that at Passover we made a little boat with baby Moses inside. We made a basket and organised the traditional Seder meal even though we had nothing to eat, but we managed somehow. On another holiday, Tu BiShvat, also known as the New Year of the Trees, we went to plant trees with the children. After the war when I visited Theresienstadt with my own children and saw those beautiful tall trees I thought of the children who planted them with me. They were all gassed.

I was transferred from the nursery school, where I worked after arriving to Theresienstadt, to the girls’ home when all the carers fell ill during a very cold winter. I was sixteen years old then. There was this little girl who had been through a lot. She witnessed the murder of her parents and brothers. She was very aggressive and kept hurting the other children. She kept beating them up and nobody knew what to do with her. I began to wonder what to do. It occurred to me I could behave in the same way to win her over. I engaged her in a rock throwing competition and I suddenly noticed that the little girl was smiling. We even climbed trees together. She would climb a tree, I would climb another and so gradually she became attached to me. When the head carer saw it she was very surprised to see I had succeeded. They couldn’t believe I was only sixteen. Perhaps I could understand her better and she got fond of me because I was so young. Then they said I could stay on in the girls’ home and become a staff member.

The little girl had a little piece of cloth she got from her mother. It was a talisman of hers. She gave it to me when she heard we were about to be transported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz. I didn’t want to take it and deprive her of the protection it gave her. She was gassed and I may have survived thanks to that little piece of cloth.

How did you get from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz?

My sister got to Theresienstadt before us. We were hoping to meet her but were told she’d been sent to Auschwitz on a punitive transport after [Governor of the Nazi Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia Reinhard] Heydrich’s assassination. Everyone transported in this way from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz after the assassination went straight to the gas chambers. However, we didn’t know that at the time and so, when we came to Theresienstadt and found out my sister had been sent to Auschwitz we said we wanted to go there as well so that the whole family could stay together. We were told Auschwitz was a labour camp and that is why we volunteered to be sent there, you see. After we got to Auschwitz we learned that she had been gassed. People who got there before us told us so.

We were transported to Auschwitz in December 1943. We travelled for several days, locked in a goods train. Instead of a toilet there was just a bucket in the corner, which spilled over because there were so many of us squashed into the carriage. Those who died during the transport were pushed aside. The stench was unbearable. The carriage had a tiny window which everyone tried to reach. When we arrived in Auschwitz the corpses were just thrown out into the snow. Of course by then the bodies were bloated and full of colours. Then they shouted the rest of us out. Everyone got a number tattooed on their arm. My number was 70882. I stayed with my mother and father. We were supposed to spend six months in the camp because the people who got transported from Theresienstadt were sent to the gas chambers every six months. When I got there, Ilona my friend from Theresienstadt was already there. She too volunteered to come because her boyfriend got transported and she wanted to go with him. She arrived in Auschwitz in October 1943. When I saw her I asked: “What’s your boyfriend doing?” and she said: “If you want to know what he’s doing, go over to the building No. such-and-such and have a look. I won’t tell you anything, go and see for yourself.” Of course I wanted to know how he was doing because he was very charming and we used to be quite friendly. When I came closer to the building I heard someone screaming and saw this friend of mine whom I used to know and who used to be a jolly, kind sort of chap beating an old Jew with a stick. I came up to him and started to yell: “What are you doing, are you out of your mind, what are you doing, stop it!” And he just gave me a look, a hyena look, and said: “Leave me alone, you think I want to starve to death? I get a piece of bread for this.” I didn’t know what to say.

All that evil made some people inhuman. They didn’t know what they were doing, because this wasn’t like normal hunger when you’d like something to eat. This kind of pain just can’t be explained. To this day, for example, I won’t leave my house without having something to eat first. When I go to sleep, I have to get out of bed in the middle of the night and eat something. And if I’m not full I feel this pain, the pain of the hunger we felt in those days.

A roll call took place in Auschwitz every morning at 5am. Afterwards we were made to load rocks onto a truck and push it to the other end of the camp. There we would unload the truck and go back while a band was playing. They were classically trained Jewish musicians. In the evening we had to load the stones back onto the truck and take them back to where they came from. We had to do this every single day. Once I heard they were looking for women to dish out the dirty black water we were given to drink in the morning. At lunchtime we had to hand out beet soup. It was the same kind of beet that was used as a fodder and it tasted horrible but there was nothing else to eat so we ate it. We would pour the soup into barrels with ladles hanging from all sides which we carried on long sticks. All of us were young and it took four of us to carry a barrel. We were rewarded by being allowed to scrape out what was left on the sides after we’ve dished it all out. I would share the scrapings with my mother.

So this is what I did. It was wintertime. We slept in wooden barracks and our block supervisor was a Pole. One day I came in numb with cold, took a wrong turn and broke her window with my barrel stick. She came out and slapped my face. I almost started to cry. Not because she slapped me but because it was so humiliating. She guarded the whole block and I didn’t want my mother to know that I got beaten as it would make her sad. But the news that the block supervisor slapped me spred like an avalanche and everyone was talking about it. When I came to our plank-bed my mother already knew it so I just smiled and said: “Never mind, at least I’ve broken her window.”

The only way out leads through the chimney

One morning in the spring of 1944 we learned that the entire September 1943 transport, the one my Theresienstadt friend Ilona arrived with, was to be gassed as six months had passed since their arrival in Auschwitz. I happened to be outside distributing food when I ran into her. I didn’t know what to do, what to say to her – she was young, healthy, alive, what could I tell her, how could I cheer her up, what could I say to her? Perhaps the only thing I could say was that I would also go to the gas chamber three months later – or not? Or not? What could I say? I think she saw me but she was looking straight ahead. In the end I didn’t accost her, I just couldn’t bring myself to do it. It’s still bothering me because I don’t know if I did the right thing or not. I don’t know, I just don’t know.

That evening was really horrible. Only those who were going to the gas chambers were allowed to go out and the rest of us were not, but we heard everything. Some of them sang as they walked, others screamed, some said nothing and simply kept walking. Then everything went quiet, we could no longer hear anything, just smelled the smoke and when we got up in the morning we saw flames coming out of the crematorium chimney. (The murder of the Czech Jews in the so-called “family camp” BIIb at Auschwitz-Birkenau on 8 March 1944 was the biggest mass murder of Czechoslovakian citizens during World War II. – Ed.)

Next morning I was going out as I was supposed to distribute tea and suddenly I saw a 100-mark note by a bunk, so I picked it up. It must have belonged to someone who lost it or threw it away on the way to the gas chambers. At the time my mother was sick with severe diarrhoea and I wanted to buy her this medicine called Tanalbin to help her. I came back after I bought it and told a friend of mine: “See, they send people to death here but then again it was like a gift from God that I found this hundred-mark note so I could buy Tanalbin for my mother.” Whereupon she broke down in tears and said: “You know, that money belonged to my cousin. She was looking for it but couldn’t find it.” I felt very guilty. I gave her some cigarettes I had bought with that money to make her feel better. My mother recovered but eventually… As we used to say – it was a kind of black humour: “The only way out leads through the chimney.”

So this is how the six months went by. There was a Kapo called Bulldog. He was a vicious man but we were fortunate enough to see him transferred to another camp later on. A German criminal took his place, a sailor who murdered someone while drunk and ended up in Auschwitz where they made him the boss of our camp. He wasn’t an anti-Semite though. On the contrary – one of the women shipped with our transport became his mistress. It might have been her doing, she might have convinced him, I don’t know but when the six months were over, he approached someone very high up and said: “You know, there aren’t enough people who can work in Germany and here we have five hundred young women who are fit to work.” So he got us away from there and we were sent to work in Hamburg. First we had to pass the selection test where we had to undress and the SS-men examined us in order to decide whether we would be sent to Hamburg or not.

What was in store for you in Hamburg?

Things weren’t much better in Hamburg except that we weren’t so close to the gas chambers and the crematorium. We had to clear away bomb ruins and clean bricks. During winter we used to commute to work by open boats. It was very cold. The only warmth was to be had near the engine room funnel so everyone wanted to sit there to get a bit warmer. Of course we all pushed each other and shoved and argued. The Germans thought it was very funny, they enjoyed the sight of us fighting for places. They would send us to all the bombed-out districts that had been abandoned and made us work there.

One day we were searching for something to eat among the ruins. We found some potato peels in an abandoned house when suddenly a chicken jumped out at us. We caught it and killed it. We managed to bring the potato peels back to the camp to boil and eat them. One day a girl found something too and brought it back to the camp but they discovered it during inspection later that day. In the evening as we lined up for the roll call the foreman made her take her clothes off and started beating her with a hose. Of course there was no way she could stand that, so she dropped to the ground and died.

One day we were searching for something to eat among the ruins. We found some potato peels in an abandoned house when suddenly a chicken jumped out at us. We caught it and killed it. We managed to bring the potato peels back to the camp to boil and eat them. One day a girl found something too and brought it back to the camp but they discovered it during inspection later that day. In the evening as we lined up for the roll call the foreman made her take her clothes off and started beating her with a hose. Of course there was no way she could stand that, so she dropped to the ground and died.

This was in Hamburg, where we lived in the port area. Later we were transferred to Neugraben which was targeted with a major air raid. The British would always drop flares before dropping bombs and we found ourselves inside the perimeter. In those days I suffered from a severe case of furunculosis. My whole face was covered in wounds and pus. The air raid took place while I was in the sickroom. There was almost nothing the doctor could do but she cleaned my face with a spoon and scraped it all out while the air raid went on. Afterwards she told me I was a hero. When I started to cry she gave me an extra portion of soup. From Neugraben we were sent to build aircrafts in Tiefstadt. When the local factory got bombed out they left us standing all night in the cold and rain. The next day they sent us to Bergen-Belsen.

I recovered as soon as I felt the Czech soil under my feet

We set out on foot for Bergen-Belsen and then we were loaded onto trains. Our journey was delayed by air raids. In Bergen-Belsen they didn’t want to take us on because they knew they would have to share with us the little food they had. About a week in the block supervisor came to tell us a table had to be delivered to the neighbouring camp. Nobody wanted to do it of course. We were so weak we had no strength left in us. But she said there would be some beets on the way and we could gather those if nobody saw us. So I volunteered along with two other women and off we went. We came to the first camp and suddenly there was a jeep coming towards us, with a white star on it. We didn’t know what it meant. We heard someone speak a foreign language other than German. And the soldier riding the jeep told us we were free now, we were no longer prisoners and could go back home.

Obviously, when I heard that, I forgot all about the table and ran back to our camp to tell everyone about it. There was no spontaneous joy though. We were all so weak we couldn’t even be happy. We just sat there picking lice out of each other’s hair when we heard shouting and saw a large group of prisoners who had torn down the fences and ran to a pile of potatoes. Everyone wanted to grab some. There were some Hungarian collaborationists there, however, and they opened fire on us. They were beside themselves with fright as they couldn’t understand we were free citizens now and they had no right to shoot at us. Eventually someone ordered them to stop. They locked them up and we were free. But many of us died even after we were liberated. We were skeletons rather than human beings. I weighed less than six stone. British soldiers who liberated us wanted to give us something to eat but all they had was canned food, which was hard to digest. I told the others: “Don’t eat this canned food, just eat bread and sugar.” They almost beat me up because they thought I wanted to keep the cans of food for myself. Many people died because we were given unsuitable food.

Later on the Red Cross arrived to attend to us. I had bad diarrhoea but I kept telling myself I mustn’t lie down because I knew I would faint. So I kept walking. I felt awful but I refused to lie down. I had diarrhoea the whole time I was in Bergen-Belsen. I recovered as soon as I felt the Czech soil under my feet.

How did your life change after the war?

After the war I lived in Prague in a home for repatriated persons. I studied to be a dental technician. There was a girl who worked in the lab. She was one year younger than me. She wanted to make friends with me but I felt we had no common language. Although we were the same age, I felt a hundred years older on account of my life experience being so different. I told myself I could live only among Jews, among people who understood me because of what we all have been through.

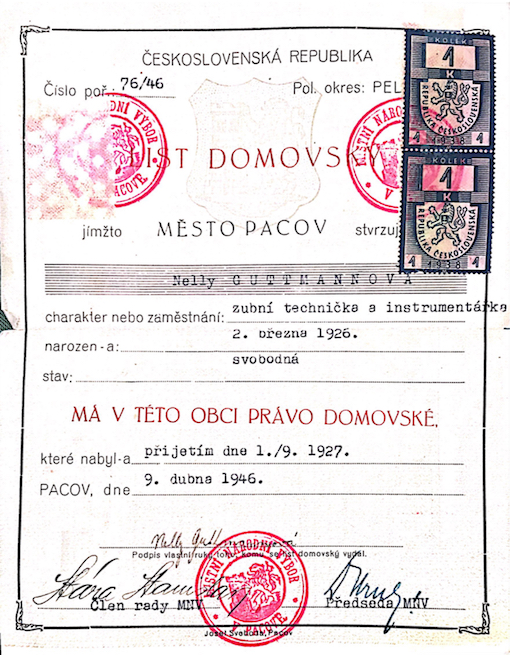

Nelly Guttmannová’s letter of domicile.

But this girl, a Gentile named Jindra Kulhánková, kept wanting to be friends with me. One day it started to rain after I went out so I hid in a passageway and I ran into her as she too sought shelter there. We started talking and she invited me to meet her parents. So I went to her house and we became friends. She said she wanted to get to know me because she’d never met a Jew before. “At school we were told that the Jews are not human beings and suddenly here you are, you dress like me, laugh like me and I can see you’re a human being just like me.” So we became really good friends. Her father didn’t like the Jews. Her mother was a devout Catholic but she accepted me and gave me a hug. When her father got to know me better he changed his mind. And I would introduce her to my friends and she became one of us. We became really good friends and kept in touch for a long time after I went to Israel. I only stopped writing to her when the communists took over, because I didn’t want to get her into trouble. We’re no longer in touch.

Do you think it’s important to keep the memory of the local Jewish citizens alive in Pacov and what do you think should be done in order to achieve that?

On the one hand I think it’s important but then again, I don’t know. Perhaps you should just make sure the future generations in Pacov know that there was a time when the Jews lived there. When I came to visit Pacov with my two sons after 1989, I wanted to show them the place we used to live. We went there and the door was locked so I rang the bell and asked permission for me and my children to take a look around the flat where we used to live. When I told the lady my name was Nelly Guttmannová, she threw her arms around me. She said she’d heard about my parents. I asked her: “Who are you? I don’t know you.” She said she was born two years after we were deported, but her parents told her about me and about my parents.

I also wanted to show my sons the synagogue we used to visit with my father. Apparently it was torn down. I’m not religious but my heart skipped a beat when I heard that. It hurt me deeply.

✡