Our website records life stories of the Holocaust survivors. They were, as in other European towns and countries, a tiny minority of the original Jewish population. We know very little or nothing whatsoever of the overwhelming majority of the Pacov Jews. However, it is important to preserve at least those fragments that remained lodged in the memory of their contemporaries and were passed on to the future generations.

Professor Hladílek remembers a Mr Gross who had a shop on Pacov’s main square. Mr Hladílek’s mother shopped there, and shortly after the occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1939, Mr Gross told her to take anything she needed for free, including soap, which had become rare during the war. Most likely Mr Gross knew the upcoming fate of Pacov’s Jews. And indeed Mr Gross lost not only his shop and the goods inside, but also his house. Vlajka, the Czech fascist organization, established their offices in his shop. Mr Gross and his entire family perished in the concetration camps. Only a photograph of one of his sons, in a Sokol uniform, survived.

Professor Hladílek remembers a Mr Gross who had a shop on Pacov’s main square. Mr Hladílek’s mother shopped there, and shortly after the occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1939, Mr Gross told her to take anything she needed for free, including soap, which had become rare during the war. Most likely Mr Gross knew the upcoming fate of Pacov’s Jews. And indeed Mr Gross lost not only his shop and the goods inside, but also his house. Vlajka, the Czech fascist organization, established their offices in his shop. Mr Gross and his entire family perished in the concetration camps. Only a photograph of one of his sons, in a Sokol uniform, survived.

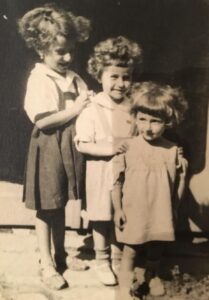

Anna was born in 1938, as was Jindřiška Schecková. Jindřiška and both her sisters Marta and Helenka had red hair after their father, Vítězslav Scheck. Anna remembers the childern playing often on Malovcova Street in front of the Jewish school where Pacov’s Rabbi was living. She recalls that one of the girls’ hair “shone like copper”. The Scheck family, both parents and their three daughters, including the youngest Helena, who was two years of age at the time of their transport, perished in Auschwitz.

Marta, Jindřiška and Helenka Schecková. From the family album of Alois Sassmann

Anna also remembers the transport to Terezín in 1942. Her father was employed as a night watchman by the community and the transport took place in the evening while he was on duty. He came home very upset as he witnessed the bitter crying of the Jewish childern. He told his wife his suspicions that “they won’t take them far, but set them down somewhere in the woods and blast them.” Anna did not understand what “blast” meant, and asked her father. Her father realized what he said and never again spoke about it in front of her.

One of the Pacov-born women remembers her grandmother who was a friend of Zdeňka Ledererová. One day during the occupation her grandmother recieved a message from Zdeňka asking her to visit. She found Zdeňka sitting emotionless in a dark room and did not understand why she had been invited to see her. Much later she realized that Zdeňka knew about the transport and had wanted to say goodbye to her. According to Zdeňka Lederer’s sister Věra, Zdenka had changed a lot after her father’s arrest by the Gestapo in 1940. The always cheerful and carefree girl, became melancholic and depressed. She felt her attendance at a dance party, forbidden to Jews, had caused her father’s arrest. Zdeňka’s father, Emil Lederer, was deported to Dachau and later to Buchenwald where he perished in 1942.

One of the Pacov-born women remembers her grandmother who was a friend of Zdeňka Ledererová. One day during the occupation her grandmother recieved a message from Zdeňka asking her to visit. She found Zdeňka sitting emotionless in a dark room and did not understand why she had been invited to see her. Much later she realized that Zdeňka knew about the transport and had wanted to say goodbye to her. According to Zdeňka Lederer’s sister Věra, Zdenka had changed a lot after her father’s arrest by the Gestapo in 1940. The always cheerful and carefree girl, became melancholic and depressed. She felt her attendance at a dance party, forbidden to Jews, had caused her father’s arrest. Zdeňka’s father, Emil Lederer, was deported to Dachau and later to Buchenwald where he perished in 1942.

We have obtained some personal identity papers and letters describing the anger and emotions of their authors, as well as those of the recipients.

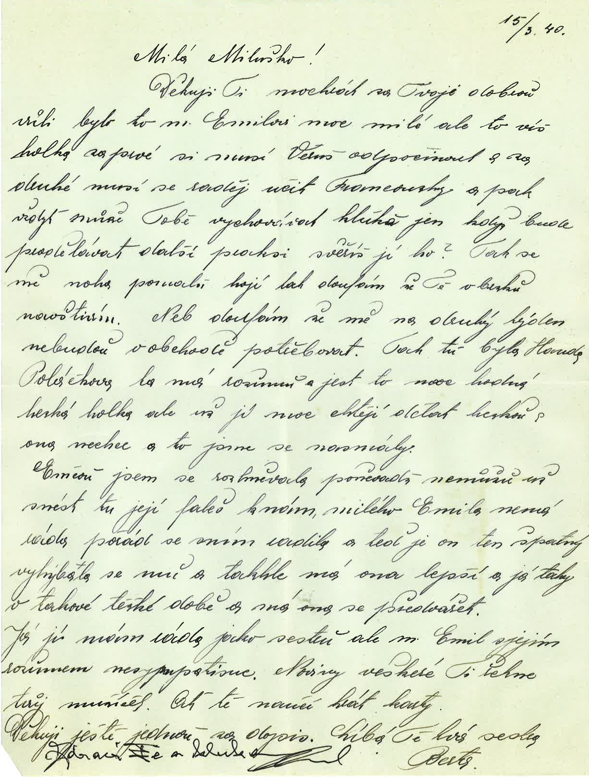

In a letter written by Berta Ledererová to her sister Bohumila (Miluška) Lustigová on March 15, 1940 (i.e. exactly one year after the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939), we can read about the concerns and tensions in the family. Though, there are also joyful parts, e.g. when Berta Ledererová writes about the visit of “Handy” or Hana Poláčková, “who is witty and a very nice and pretty girl, but her parents want to make her even prettier and she does not want to, so we had a good laugh.”

Berta Lederer’s letter dating from March 15, 1940

Berta Ledererová further expresses thanks to her sister Miluška, who offered Věra (Berta’s daughter) the opportunity to earn some money as a baby-sitter of her little son Jiří, born in December 1939. Věra had just finished nursing school in Prague in the spring of 1940. Her mother wanted Věra to rest and learn French. Berta Ledererová did not know then that her husband would be arrested in two weeks. Věra Ledererová did learn French and later she used her knowledge in the Christianstadt Labor Camp where she was sent in 1944 from Auschwitz. At Christianstadt she tried to contact French war prisoners, but was punished and re-assignened to even harder work. Jiří Lustig, his mother Bohumila Lustigová, and Berta Ledererová perished in Auschwitz.

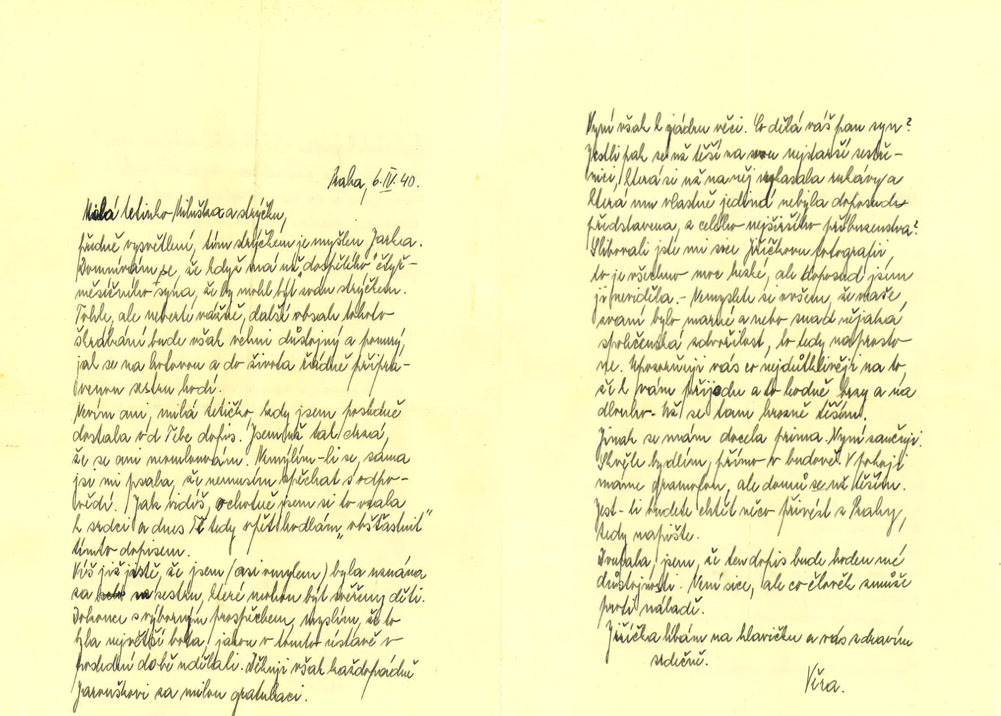

Věra Lederer’s letter dating from April 6, 1940

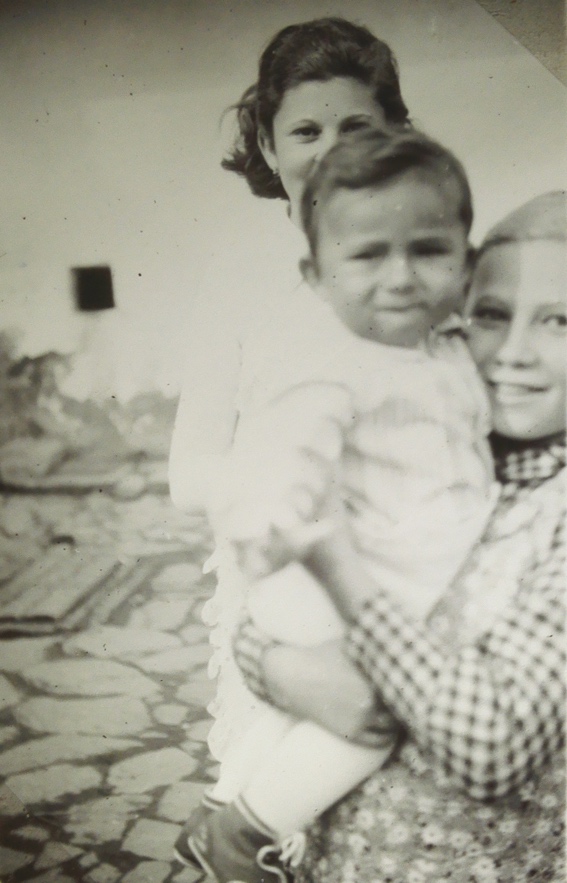

Věra Ledererová’s letter dates from the same time, i.e. spring 1940, when she finished her studies in Prague. She writes of herself with a sound irony as of a “mature and life-ready nurse” and a “nurse in whose hands children can now be entrusted”. She looks forward to Pacov, although she “lives comfortably” in Prague and there is a gramophone in their room. Soon, she as a Jew, would not have the right to posess any radio set or musical instrument. She looks forward to seeing her nephew, Jiříček, and she impatiently awaits for a photograph of him. A photo of little Jiří Lustig survived in a family album of Lederer family. He perished in Auschwitz concentration camp.

Věra Ledererová’s letter dates from the same time, i.e. spring 1940, when she finished her studies in Prague. She writes of herself with a sound irony as of a “mature and life-ready nurse” and a “nurse in whose hands children can now be entrusted”. She looks forward to Pacov, although she “lives comfortably” in Prague and there is a gramophone in their room. Soon, she as a Jew, would not have the right to posess any radio set or musical instrument. She looks forward to seeing her nephew, Jiříček, and she impatiently awaits for a photograph of him. A photo of little Jiří Lustig survived in a family album of Lederer family. He perished in Auschwitz concentration camp.

Some of the letters mirror the life before the war with its everyday duties and concerns, free of any signs of future tragedy.

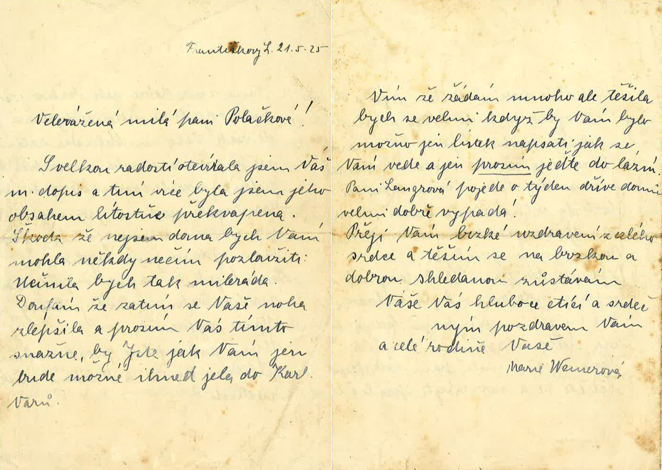

Marie Weinerová recommends to Mrs. Poláčková, in a letter dating from 1925, to visit Carlsbad in order to cure her leg as “Carlsbad is the best cure and all money spent on doctors means throwing it out the window”. She adds that “Dr. Autengruberová and Mrs. Langrová who came home one week earlier, look very well! They stayed in Carlsbad, too.” Marie Weinerová and her daughters, and Hermína Langerová also perished in Auschwitz.

Marie Weinerová’s letter dating from May 21, 1925

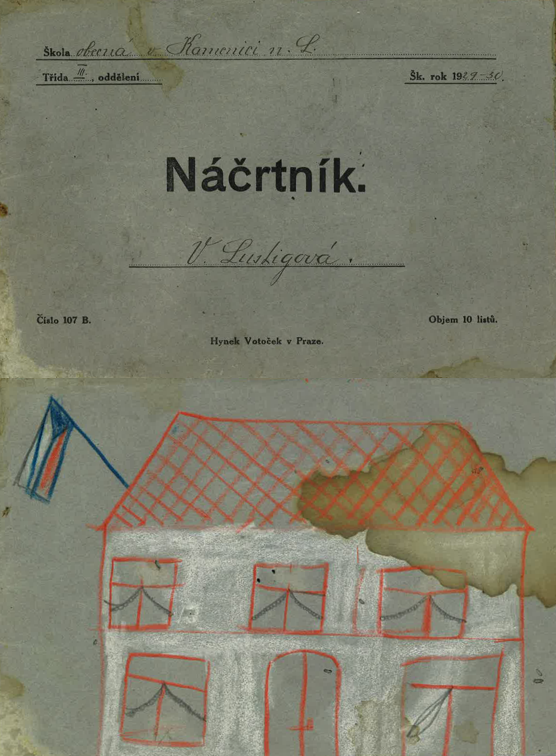

Sometimes only fragments survived, e.g. a pre-war children’s drawing from a primary school notebook, signed “V. Lustigová” (Kamenice nad Lipou).

We are sadly unable to draw detailed portraits of all the people mentioned here but it is important to preserve their memory even in such tiny fragments of their tragically terminated lives.

✡